An Australian epidemiologist's memories of Tibet

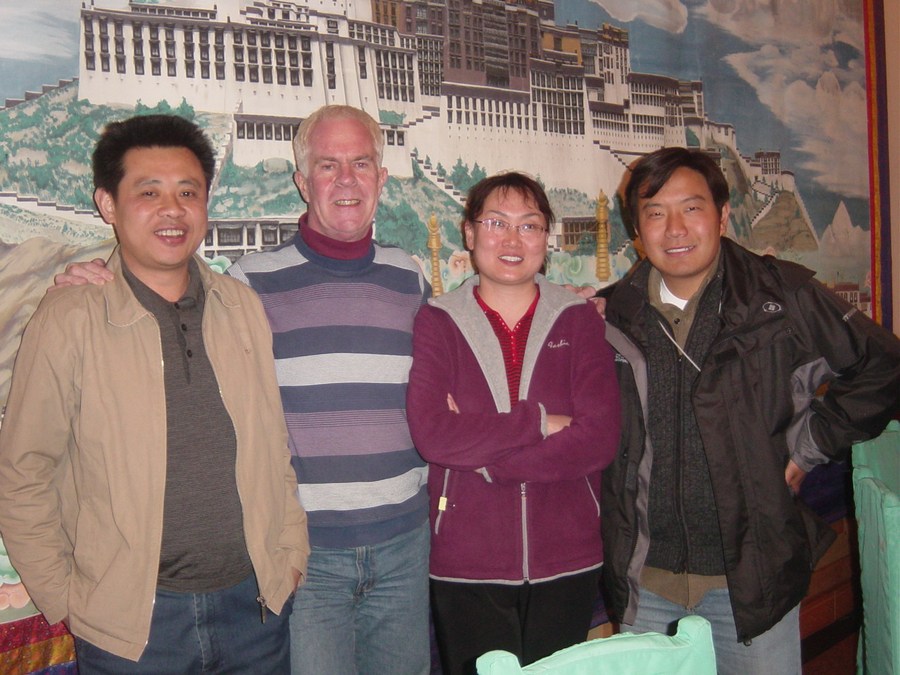

Photo shows Mike Toole working with Chinese colleagues in southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region. (Xinhua)

Mike Toole, an epidemiologist from Australia, has dedicated 20 years to improving health facilities and training professionals in Tibet, bringing care and comfort to the local people. During his travels, Toole also witnessed big changes in Tibet.

CANBERRA, May 12 (Xinhua) -- In Australian epidemiologist Mike Toole's office in Melbourne there are several door curtains he brought back from Tibet.

With delicate embroideries, the handmade curtains were a traditional handicraft in the southwestern China's autonomous region, which Professor Toole has visited more than 20 times.

During the past two decades, the associate principal research fellow from Australia's medical research institute Burnet has worked in Tibet, helping to improve local health facilities and train professionals. "There were big changes," he said.

The first project in which Toole got involved in Tibet was the Shigatse primary health care and water project, which began in late 1997 in partnership with the Australian Red Cross and lasted for four years.

"Burnet, which led the technical side of the project, worked very closely with the Shigatse prefecture health bureau, and together we constructed a health center in each of the townships, as well as about 20 village clinics," he recalled.

They also helped to renovate and upgrade hospitals, and did a lot of training in various aspects of health care in Shigatse.

Photo shows Mike Toole conducting training sessions for local medical staff in Shigatse, southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region. (Xinhua)

While they were conducting research, they found something common among villagers: many had low back pain. "We were able to bring in a physiotherapist from Australia, who did a survey and found a very high prevalence, especially among women," recalled the professor.

They found that it could be caused by women bending over and picking up large weights, including containers of water which could hold as much as 40 liters.

So they designed what they called the "back-happy tap stand," which meant that women didn't have to bend down to lift water.

"They could put the bucket on a ledge, turn on the tap, and then just turn around and put the container on their backs," Toole explained.

He showed Xinhua a photo, in which an old lady in traditional Tibetan robe stands by a cement ledge and the bucket on her back is right underneath a tap. An article of the design could still be found on the website of Lancet, one of the world's best medical journals.

Photo shows the previous water fetching device in southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region, local villagers need to bend down to lift water. (Xinhua)

Infant and maternal mortality used to be high in Tibet because traditionally women gave birth to babies at home. Another program Toole worked for in Tibet focused on training local midwives, who would provide expert care to women at home, and try to persuade them to go to hospital.

He noted that local doctors and nurses in Tibet worked very hard, and governments from the prosperous eastern part of China offered help to the autonomous region.

Photo shows the "back-happy tap stand" designed by Mike Toole and Burnet Institute to help local villagers avoid bending over when lifting water in southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region. (Xinhua)

For instance, he remembered that the Shanghai government provided funding to renovate hospitals in Shigatse. "There was much improvement in those years," he said.

In fact, during the past decades, the Chinese government invested heavily in developing Tibet. According to a white paper by the China's State Council Information Office in May 2021, from 1994 to 2020, the provinces and equivalent administrative units, central government departments, along with state-owned enterprises directly under the central government, provided support to Tibet in the form of paired assistance through 6,330 projects, representing a total investment of 52.7 billion yuan.

During his years in China, Toole saw progress in health care in Tibet. "I saw increasing confidence," he said. He saw local health authorities taking a lot more responsibility, developing their own priorities while working in line with the national guidelines.

"You can see that by the very low infant mortality, children mortality and maternal mortality statistics," the professor added.

Photo shows Mike Toole meeting with Chinese colleagues from local health department in southwest China's Tibet Autonomous Region. (Xinhua)

The death rate of women in childbirth has dropped to 48 per 100,000 live births, and the infant mortality rate to 7.6 per 1,000 in Tibet, according to a report by China's State Council Information Office in 2021.

In fact, Toole, who first traveled to China in 1979, has seen China's development in other aspects as well.

Recalling his first visit, he said it was at the very early days of opening up, "the things I noticed most were the clothes people wore, and the cars. In 1979, everyone was riding a bicycle and there were a few trucks and buses."

Then he saw Lhasa growing into a modern city, with high-rise buildings, cars, and people wearing fashionable clothes.

In general, he said it was very enjoyable to work in Tibet as he was attracted by its unique culture. "We visited many beautiful monasteries," he said.

His most recent involvement with China was co-designing a China-Australia-Papua New Guinea trilateral malaria project, during which he traveled to Beijing and Shanghai in 2019.

"Australia provided most of the funding while China provided most of the expertise," he said. "The coronavirus made it very difficult to implement the program, but it's back on track now."

In retrospect, the epidemiologist observed that academic institutions in China and Australia always had very good relationships. "It's been going on for a long time," he said. "It's been very fruitful."

"We have common interests," he concluded. "There are areas where we could work together," he said, referring to diseases such as hepatitis, tuberculosis and 'lifestyle diseases' such as diabetes and cancer.