Qinghai-Tibet Plateau research offers insight into effects of climate change

Alpine wetlands in Shanza county in the Xizang autonomous region. (CHINA DAILY)

Editor's note: As protection of the planet's flora, fauna and resources becomes increasingly important, China Daily is publishing a series of stories to illustrate the country's commitment to safeguarding the natural world.

Having roamed the wilderness in Shanza county on the northern hinterland of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau for more than 15 years, Tsultrim Tharchen, a wildlife ranger, can see with ease the distinct changes brought by warming temperatures.

"The pasture grass grows significantly taller now than before, and I'd never seen so many wildflowers in the past," he said, pointing to clusters of tiny, jewel-like blossoms in purple, yellow, and white dotting the steppe.

Situated at an average altitude of 4,700 meters, the county used to be inundated by harsh winds, making a motorcycle ride in winter punishingly cold for Tsultrim Tharchen. "Nowadays, winter feels not so hard to get through," he added.

The observations of Tsultrim Tharchen encapsulate the very basics of climate change on "the roof of the world". The geologic expanse defined by majestic mountains, pristine lakes, and long, dry, and frigid winters is getting warmer and wetter.

While local residents like Tsultrim Tharchen rely on their senses to take the pulse of the plateau, a group of Chinese researchers has utilized scientific equipment and multidisciplinary expertise to survey the land's response to climate change.

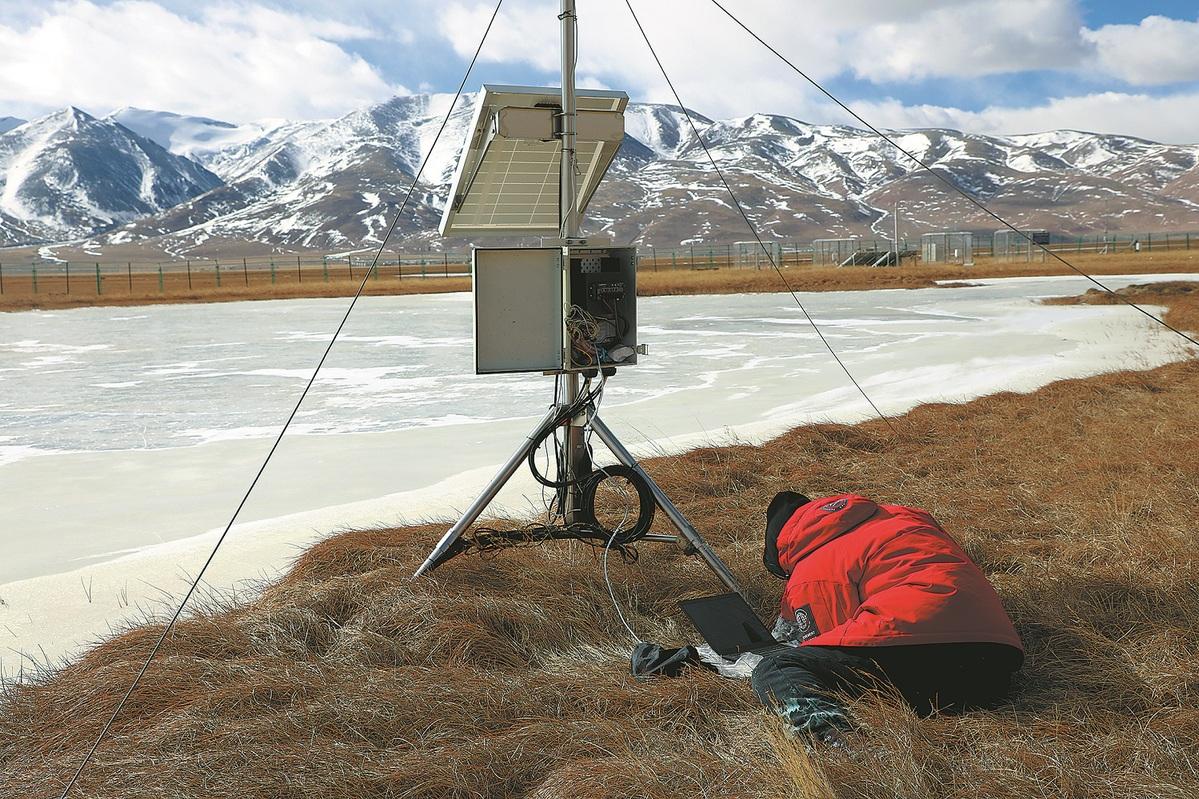

A researcher retrieves data from a monitoring device in Shanza. (CHINA DAILY)

For over two decades, researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment have been collecting and analyzing ecological data.

Together with other institutes at the CAS, they have set up more than 30 monitoring sites, scattered across the plateau from the Zoige grassland near its eastern edge to the western county of Rutog bordering India, as well as from Dromo county on the southern tip to Hoh Xil nature reserve in the north.

"What we have done in essence is put a stethoscope on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau to constantly monitor its breathing," said Wang Xiaodan, a researcher at the institute.

A crucial part of their research rests on measuring the plateau's emissions and absorption of carbon.

Deemed a significant ecological barrier in China, the plateau has a mix of ecological zones represented by glaciers, permafrost, lakes, rivers, alpine meadows, and forests, which are used as sites to study carbon processes in various terrestrial ecosystems.

The region's diverse terrain has enabled it to function as a carbon sink — meaning it absorbs more greenhouse gases than it emits.

However, global warming and climate change have sparked concerns that the thawing permafrost on the plateau could release enormous amounts of greenhouse gases.

Further complicating the picture is whether a series of ecology preservation projects carried out in the region could impact its carbon storage capability, researchers added.

Researchers evaluate changes in carbon dioxide concentrations under rising temperatures in Shanza. (CHINA DAILY)

A monitoring station in Shanza county has been the world's highest-altitude comprehensive ecological monitoring facility since 2010. It has three laboratories specializing in biology, soil, and water, as well as 33 hectares of alpine grassland and 6.7 hectares of alpine wetland that it monitors.

Wang, who is also head of the station in Shanza, has spent more than two decades surveying the ecosystems of the plateau.

"In the early 2000s, it would take us several days to reach Shanza, first flying from Chengdu to Xizang's regional capital of Lhasa and then driving all the way to Shanza through Shigatse city," he said. "We had to eat instant noodles and canned food for days and spend nights in tents in the wilderness."

But the long and strenuous trips were always worth it.

"The grasslands in Shanza represent the largest and most sensitive alpine grassland ecosystem of its kind," he said. "Within a 5-kilometer radius around the station, there are three types of grasslands, wetlands, and lakes, enabling us to carry out comprehensive research."

Wang Zhuangzhuang, a researcher at the institute, said he visits the monitoring station several times a year to retrieve data stored in the hardware there.

An example of their research is gauging the effects of installing fences that limit areas for livestock grazing on a piece of land's carbon absorption rate, he added.

In Lhokha city — about a two-hour drive from the regional capital of Lhasa, is a monitoring site for the carbon sequestration of artificial forests.

In the past, the city that sits along the Yarlung Zangbo River was frequently beset by dust storms, prompting a drive initiated in the 1980s that resulted in over 45 million trees being planted over four decades.

A new monitoring site, aimed at evaluating the forests' ecological role, was put into use this year.

"Our research can help shed light on the optimized ratio of male and female tree species to maximize improvements in soil condition, address problems such as pests, floating fluff, and bolster preparedness for potential issues such as invasive alien species," said Wang Xiaodan.

Zhou Ping (right), a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, observes the effects of sand-fixing vegetation at a trial plot in Lhokha city with her students in late July. (WANG XIAOYU/CHINA DAILY)

Less than an hour's drive from the site is a plot of experimental land dedicated to desertification research.

"We are conducting transplant experiments on grass and shrubs here to test their resistance. By evaluating their growth and winter survival rates we can select plant varieties that are suitable for growth in alpine sandy areas," said Zhou Ping, a researcher at the institute.

Scientists at the institute are providing insights into the plateau's role as a carbon sink.

Researchers found that 26 out of 32 monitoring sites were still significant carbon sinks from 2002 to 2020, and that the carbon absorption rate was more substantial than previously thought.

"The strongest net carbon sink effect along the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau occurs at an altitude of 4,000 meters," said Wei Da, a researcher at the institute who coauthored a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a peer-reviewed journal of the academy in the United States.

"Our study has determined that the alpine ecosystems on the plateau remain a powerful carbon sink. The consistently warm and wet climate on the plateau is conducive to plant growth and can drive stronger carbon sink effects," he said.

In another study that was released in Nature Communications, an open-access international journal this year, researchers found that high-altitude and colder ecosystems, including the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, are more sensitive to climate warming than terrains at a lower elevation.

By combining machine-learning tools with monitoring data and climate change analysis models, the study concluded that high-elevation environments respond consistently to a warming climate and may play a positive role in mitigating the effects of climate change.

"Climate change in mountainous areas and human activities are extremely complicated, and go well beyond our existing knowledge," said Wei.

He said that questions such as how much carbon emissions will result from thawing permafrost, the impact of extreme weather on curtailing plant growth, and how to regulate and improve carbon sinks remain unanswered.

"The closer we are to the mountains, the more questions emerge," said Wei. "But these unknowns also motivate us to keep advancing research."